December 02, 2004

Oil: Stocks vs. Capacity

By Ian

The recent decline in prices for a barrel of oil seems to be good news for the stock market. No surprise there. But a lot of the commentary in such articles has gotten me thinking. A good deal of the concern is over the stock of oil products. From a WaPo story:

"Oil futures go down, stocks go up. I think that'll be a pattern for a long time, and the good news is that if we keep getting inventory reports like this, oil prices will be ready for a big correction downward," said Brian Belski, market strategist at Piper Jaffray. "Overall, this market has clearly turned to a growth mode over the past few months, and should continue to grow."Stocks of oil and oil products are generally taken as a sign of ability to deliver products on demand when such things as heating oil are needed during the winter. When they're low, the view is that things are getting a bit thin and any unforseen uptick in demand is going to stretch the stocks too far pushing the prices way up. This has been a contributing factor to the recent per-barrel oil prices. From the EIA, here's an illustration of recent stock levels for crude oil:

Sitting at or below average for the first half of the year, then dipping back down again, has helped drive the spot price for WTI up to the levels where it became a campaign issue. So the slide back down can be read as a sign that people have a bit more confidence that our ready supply of oil (as opposed to having to wait for more to be pumped and imported) is going to suffice for the coming months. And, as much as there was a lot of talk about oil reaching new and amazing heights in price, the recent moves have prompted talk of a "correction" to get rid of the "fear premium".

Some of the fear, and thus the escalating prices, is due to political factors in the world. Nigeria had civil disturbances, there were labor strikes in the Netherlands, and Iraq is, well, Iraq. But none of that is really new. We've seen it before, and if recent finds in former Soviet Union countries are any indication, the world will continue to face an oil supply rooted in the world's most unstable regions.

Something I tend to think is under-discussed, at least in the popular media, is the issue of refining capacity. While Saudi Arabia is still the world's swing producer, with the largest amount of excess production capacity (they can turn the spigots on faster and wider than anyone else), having more crude sloshing around doesn't help much if you can't do anything with it. In cases of demand spikes or making up for disruptions in supply, the measurement for being able to smooth over the shake up isn't the amount of oil that can be pulled out of the ground, it's how much oil can be turned into usable things like gas, fuel oil, heating oil, and other distillates.

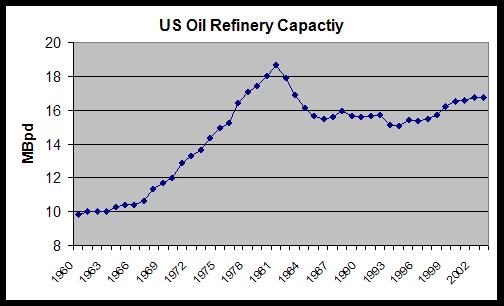

The US hasn't had a new oil refinery come on-line since 1976. Which helps explain this (data from the EIA):

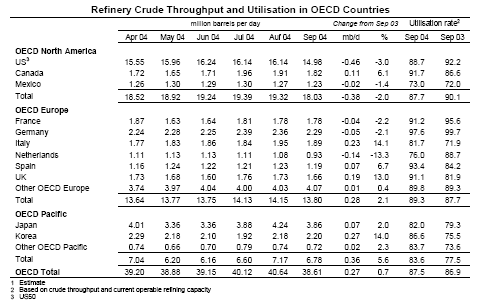

Two things of note, then: 1) the US demands over 20 million barrels of oil a day, and 2) US refineries are running around 90+% of capacity for each plant. This means that, in events like the four hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico this year (where a large portion of US refining is done) there's little ability for other plants to pick up slack while some refineries are down. And the US isn't the only one pushing its limits. This report from the IEA has one illuminating table (among others):

A number of OECD countries are running at higher capacity rates than the US, especially over the 2003 timeframe. (The US number from Sep 2004 has risen sharply again.)* Since the cost to move crude to the point of refinement is so much lower than the cost to move distillate fuels -- which is why we have refineries here that have capacity far beyond the ability of Texas to pump out oil -- widespread stress on refining capacity means delays in getting products to final distribution to consumer; delays in things like heating oil for the winter (thus the so-far mild temperatures for the winter have had calming effect). Also mentioned in the report is an interesting mismatch between those kinds of oil that are seeing an increase in demand (light/sweet) vs. those that are being pumped out of the ground (heavy/sour). The mix of refineries available to us here in the US isn't well-suited to accomidating such changes.

All this has a direct impact on the stocks of oil, since the refineries are essentially how the stocks get filled. Overtaxed refineries can't react well to interruptions, which means that even small shocks get magnified through the system.

"Oil independence", as it's usually considered, is a pipe dream so long as the US uses oil, and someone, somewhere can pump and ship oil for less than it takes to get it from Texas. But that doesn't mean the US has to be so sensitive to shocks. Having more excess refining capacity (or any at all) might be one way to help smooth things out. Too bad, then, that building new refineries is almost entirely out of the question. The return on investment for refining has actually gotten better, but the regulatory and environmental restrictions (more on the environmental issues here), including nearly 800 permits to secure and reductions of 42% of actual profitability against posited levels without environmental regulations, place it out of reach for any of the "majors". Even if large amounts of capital for investment could be obtained, companies would immediately begin fighting the traditional NIMBY problems of any large industrial facility; it's no wonder US refinery building has gone the way of the dodo**.

And so while it's not entirely certain that high oil prices have a negative impact on the world economy (definitions of "sustained" and 'high", and assumptions about behavior make analyses like this fragile), the addition of refining capacity might be, at least, a hedge against the problems that arise from being so sensitive to fluctuations that are beyond our control.

*Some might notice that I said the US uses over 20 million barrels of oil a day while this chart shows that US refining capacity hit 16.25 million barrels a day. This is how stocks move into the lower edge of the average range, as demand not only surpasses refining capacity but also restricts the amount that can be placed in stocks. Either the US continues to draw down stocks, making the market even more nervous, or the US imports refined products, a relatively expensive alternative.

**Though, unless I'm mistaken, the dodo wasn't regulated out of existence.

UPDATE: My apologies for the misspelling in the "capacity chart". It was a casualty of doing the post over lunch. And, for data about capacity, click here and open the XLS file. The US is up to running around 94% for the week of Nov. 26.

It turns out to be a far more complex set of interactions than simply Oil down,. stocks up. Markets (and most entities governed in part by the rules of Chaos) are far more complex than controlling for a single variable.

Earlier this week, I pondered the question: "What if Oil was at $30 instead of $50 per barrel?"

You can see the results here:

http://bigpicture.typepad.com/comments/2004/11/what_if__1.html

Certainly. I don't mean, and I don't believe I suggest, that there is one and only one relationship here. I'm more concerned with the varying discussions about the changes in the price of oil. A good portion of the popular discussion revolves around stocks of oil, while I tend to see more importance in the question of refining capacity, since the dip to the bottom of an average range of stocks doesn't, I would think, communicate a sudden screeching halt to industry as the oil dries up.

Comment by Ian at December 4, 2004 06:46 PM | Permalink

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://truckandbarter.com/mt/mt-tb.cgi/315